Project 5 — Sand

In this project we’re going to work with a 2D world of rocks and sand. Behind the scenes, we’ll build this with a grid. We will supply you with all the code that does the animation and handles mouse clicks. You will write code to handle the logic of manipulating the grid.

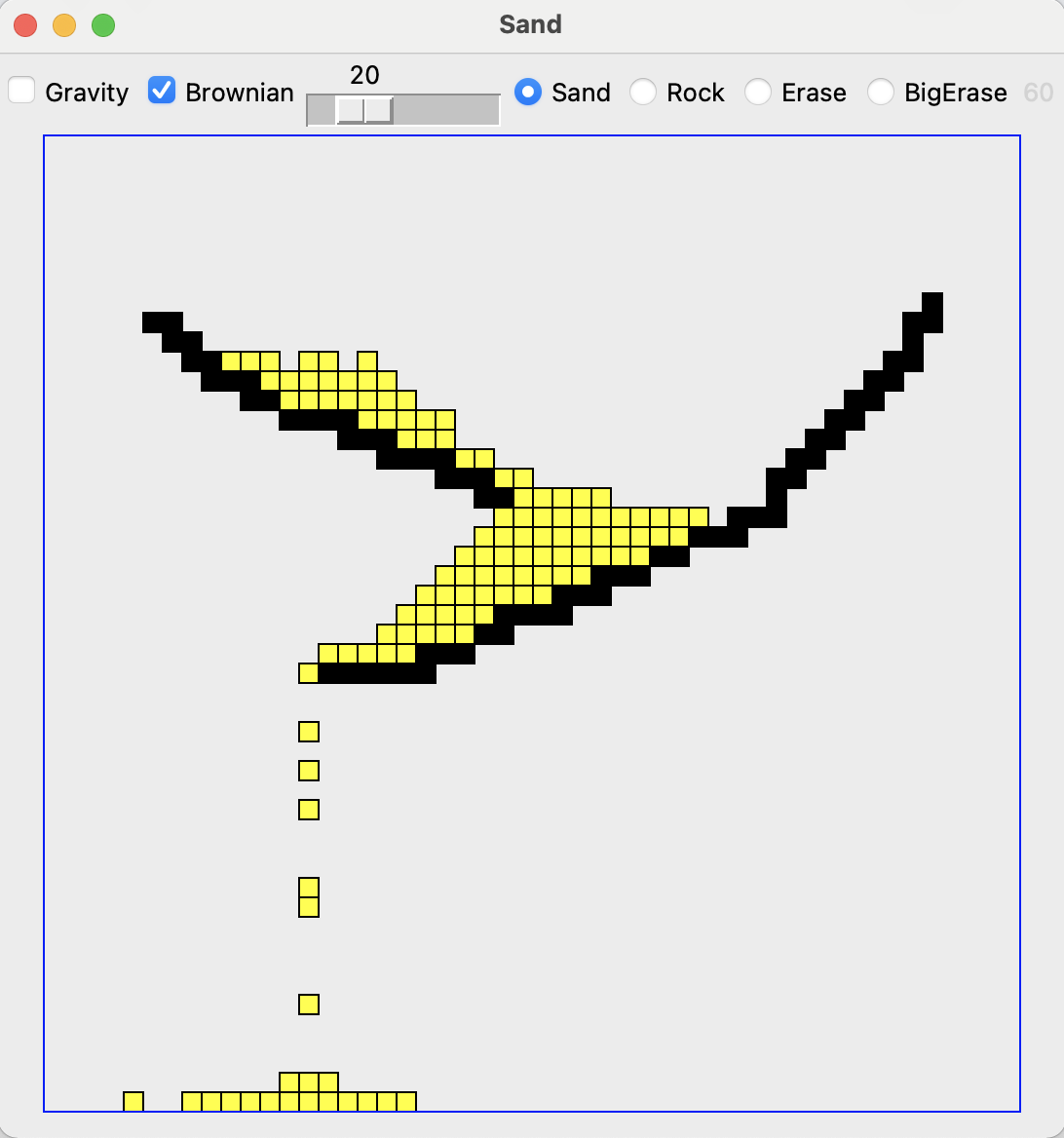

In this program, there are rocks (black grid squares) and sand (yellow grid

squares). You can draw rocks and drop sand by clicking with your mouse. Inside

the grid, we indicate sand with the letter 's' and rocks with the letter

'r'.

Sand movement rules

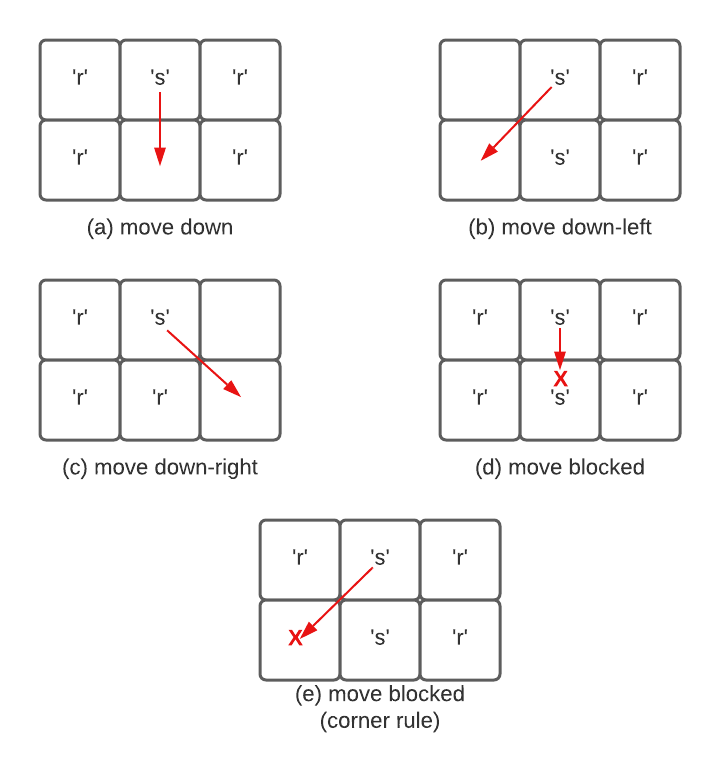

Sand always moves down into an empty space. The figure below shows examples of how sand can move.

In example (a), sand can move straight down into an empty space. In examples (b) and (c), sand can move diagonally down into an empty space. In example (d) the sand is blocked if the space below it is not empty. In example (e), the sand is blocked from moving diagonally if the space above the destination is not empty. This last example is known as the corner rule.

We will move the sand down in the following order:

- sand will move straight down if possible

- sand will move diagonally left if possible

- sand will move diagonally right if possible

If none of these apply, the sand won’t move.

Setup

To get started, download project5.zip. You will write all

of your code in the file sand.py. We’ve conveniently placed these all at the

top. The bottom contains code you don’t need to modify.

To get this working, we’ll use the same divide-and-conquer strategy from the labs. We will divide the large program into many functions, and use Python’s doctests to test each function in isolation before moving on to the next function. You need to write four (4)) functions to make the whole thing work.

For each function, we have written the function declarations, documentation, and some of the doctests. In some cases you will need to write more doctests.

To be successful, write one function at a time, in the order shown, and be sure the function passes all of its doctests before moving to the next function.

Do a move

The do_move(grid, x_from, y_from, x_to, y_to) function moves sand from

(x_from, y_from) to (x_to, y_to). We have written this function for you.

This function assumes the move is possible. You will write functions to check

that move is indeed possible.

Is a move OK?

Write the function called is_move_ok(grid, x_from, y_from, x_to, y_to). This

function checks whether it is OK to move a piece of sand from (x_from, y_from)

to (x_to, y_to). Assume there is sand at (x_from, y_from) and that this

location is in bounds. However, you need to check all the rules for moving sand

we discussed above. For a move to be OK:

- the destination must be in bounds,

- the destination must be empty, and

- for diagonal moves, the move must not violate the corner rule.

We have provided some tests for first case above. Add at least 2 more tests, trying some of the other cases.

After this, the doctests make a 3 by 2 world and include one test showing that the left move from (1, 0) is OK:

>>> grid2 = Grid.build([[None, 's', 'r'], [None, None, None]])

>>> is_move_ok(grid2, 1, 0, 0, 0) # left ok

TrueAdd at least 4 more tests, trying each of the other four directions: right, down, down-left, and down-right. You should have at least one test of the empty and corner rules, and tests with a mixture of True and False results.

Reminder: We want to check that straight left or right move is OK (according to the first two rules) because as a last step we will write a randomized function that moves sand right or left.

Once you have the doctest written, complete the function. You should probably use the pattern of early returns for False cases, and then a default case that returns true.

Use the doctests as you work out the code. Sometimes a test fails because the function is wrong. Other times, upon review, you realize that your test is wrong, not spelling out the correct grid state. This is a normal sorting out of your code and your tests that professionals work out with real code.

Do gravity

Write the function called do_gravity(grid, x, y). This function is given a

coordinate (x, y) that you can assume is in bounds. The function then checks

if there is sand at this coordinate. If there is, it tries to move it, trying

the following moves in order:

- sand will move straight down if possible

- sand will move diagonally left if possible

- sand will move diagonally right if possible

In some cases, the sand can’t move. In all cases, return the grid. Remember, you can do an early return for an obvious case that should not do anything.

Use the helper functions written above this code to do most of the work. This is a good illustration of decompostion! We provide a rich set of doctests for this function.

Do the whole grid

Write the function called do_whole_grid(grid, brownian). Ignore the brownian

parameter for the moment. This function loops over all the squares in the grid

and does one round of moving sand in each location where it is possible. The

function returns the grid when done.

First, write two tests, with at least one test featuring a 3x3 world with sand

at the top row. In your tests, pass 0 for the brownian parameter when you call

do_whole_grid().

Once you have your tests, write the code for the function. You must be careful to loop from the bottom up, just like we did in the waterfall problem. Remember, you can use the following to loop over the y values in reverse order:

for y in reversed(range(grid.width))It doesn’t matter whether you loop over the x or y values first.

What’s wrong with regular top-down order? Suppose the loops went top-down, and

at y=0, a sand moved from y=0 down to y=1 by gravity. Then when the loop

got to y=1, that sand would get to move again. Going bottom-up avoids this

problem.

Run your doctests in do_whole_grid() to make sure that your code is working

correctly.

The do_whole_grid() does one round of movement for the world, calling

do_gravity() a single time for each square. The provided GUI code calls this

function every millisecond when the gravity checkmark is checked to make the

game run.

Milestone

Once you have do_whole_grid() written and tested, along with all the other

functions listed above, you can try running the whole program. You can do thsi

with:

python sand.pyClick the rock or sand buttons and then click the mouse button to scribble rocks or sand onto the world. Gravity should work, but brownian is not done yet. There are also buttons for erasing and a big eraser.

Normally when a program runs the first time, there are many problems. But here we have used careful decomposition and testing, so there is a chance your code will work perfectly the first time. If your program works the first time, try to remember the moment. On projects where code is not so well tested, the first run of the program is often a mess. Having good tests changes the story.

Brownian motion

Write the function called do_brownian(grid, x, y, brownian).

Brownian motion is a physical process first documented by Robert Brown, who observed tiny pollen grains jiggling around on his microscope slide.

For our sand project, we’ll use Brownian motion to say that there is a

probability that sand at location (x, y) will randomly move one square left or

right. The “brownian” parameter is an integer in the range 0..100 inclusive: 0

means never do a brownian move, 100 means always do a brownian move. This value

is taken from the little slider at the top of the widow, with the slider at the

left meaning brownian=0 and at right meaning brownian=100. The doctests are

provided but you write the code.

Here are the steps for brownian motion in the sand world:

-

Check if the square is sand. Proceed only if it is sand.

-

Create a random number in the range

0..99. Remember you can userandom.randrange()for this. Proceed only if the random number you choose is less than thebrownianparameter. In this way, for example, if brownian is 50, we’ll do the brownian move about 50% of the time. -

Choose another random number in the range

0..1, like flipping a coin. If the coin is 0, try to move left. If the coin is 1, try to move right. Remember, this move can only succeed if the move is legal. Use your helper functions to check if the move is possible and do all the actual work. Don’t try both directions. Pick one direction with the coin, try it, and that’s it. In this way the Brownian motion is left/right symmetric.

Testing the Brownian motion

Testing an algorithm that behaves randomly is tricky. We have a little hack in

the do_brownian() doctest code that enables docests there. The doctest

includes the following line of code :

>>> # Hack: tamper with randrange() to always return 0

>>> # So we can write a test.

>>> # This only happens for the Doctest run, not in any other case.

>>> random.randrange = lambda n: 0Essentially, this is saying: I know you have a fucntion you call to generate random numbers. But instead of calling that function, call this function:

f(n) = 0In other words, this line modifies the normal random.randrange() function so

it returns 0 every time. The lambda keyword is a fancy way of writing f(n).

We won’t cover lambda functions in CS 110 but you’ll see them in CS 111!

Note this only affects the doctests. When we run our code normally, we will get

the usual random numbers from randrange().

Try out your Brownian motion

Edit the loop body in do_whole_grid() so that after you call

do_gravity(grid, x, y) you also call do_brownian(grid, x, y, brownian). So

for every cell (x, y), from the bottom of the board up to the top, you will

first run gravity to move some sand and then run the Brownian motion to

potentially move some sand left and right.

Try running the program with brownian switched on and move the slider around.

Command line options

You can control a variety of other aspects of the game with command line arguments. This is the full set of arguments:

--width: sets the width of the board (default 50)--height: sets the height of the board (default 50)--speed: number of ms between rounds (default 1)--scale: scales the size of the squares (default 10)

You can use the following to get a reminder of the possible arguments:

python sand.py -hFor example:

python sand.py --scale 4 --width 100 --height 100 --speed 100Frames per second

The Sand program is pretty demanding on your computer. It runs a lot of computation without pausing. You may notice the fans on your laptop spinning up. At the upper right of the window is a little gray number, which is the frames-per-second (fps) the program is achieving at that moment, like 31 or 52. The animation has a more fluid look with fps of, say, 50 or higher.

The more grid squares there are, and the more grains of sand there are, the slower the program runs. For each gravity round, your code needs to check every square and every grain of sand, then potentially move the sand. By making the world large or by adding lots of sand, the fps of the game should go down. Play around with different grid and pixel sizes to see how this affects the fps.

Submit

You need to submit:

sand.py

Points

This project is worth 60 points.

| Task | Description | Points |

|---|---|---|

is_move_OK() doctests | You have added 6 doctests | 10 |

is_move_OK() | Your solution works | 15 |

do_gravity() | Your solution works | 15 |

do_whole_grid() | Your solution works | 5 |

do_brownian() | Your solution works | 15 |

Credits

This assignment is based on an assignment built by Nic Parlante for CS 106A at Stanford. This in turn was based on an assignment by Dave Feinberg at the Stanford Nifty Assignment archive.